Notes from Harvar: A descriptive and evaluative observation of a VHSNC meeting

This blog is part of the series of blogs on Aspur Project under the Primary Healthcare Initiative (PHI), a partnership between Basic Healthcare Services and Centre for Healthcare.

It was an early pre-monsoon morning when we set out to study and observe the functioning, community participation, and initiatives implemented by the recently activated Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC) in Harvar village of Aspur Block. The VHSNCs, as an intervention, were introduced by the National Rural Health Mission to take collective actions on matters related to health and its social determinants at a village level [1]. Although initiated in 2005, VHSNCs were not active in the Aspur block until a year ago. In March 2021, Basic Health Services (BHS), an NGO providing high-quality and responsive primary healthcare to marginalized and vulnerable communities in rural Rajasthan, activated VHSNCs in the Aspur block as part of a UNICEF-supported project to strengthen the public health system and health care delivery along with the Centre for Healthcare at IIM Udaipur [2].

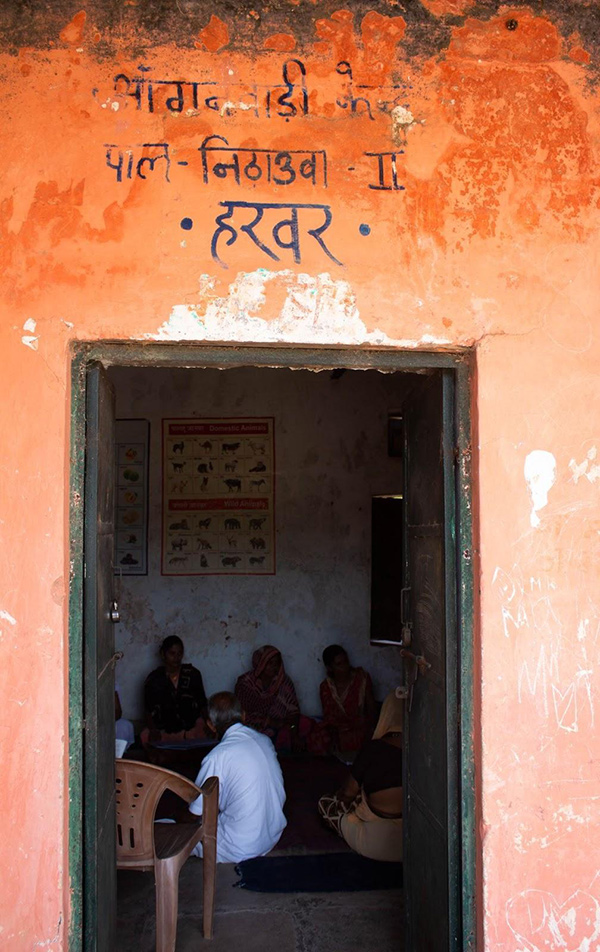

As we descended from the car at Harvar village, we carefully trod along an elevated gravel track leading to a small nondescript room. Aanganwadi kendra, Pal Nithawua, Harvar read the scrawly but fairly decipherable words hand-painted in devanagari on the pale pink facade of the building. From the room’s old and worn-out interior walls hung teaching aids and picture charts of modes of transport, parts of the body, and geometric shapes, among others.

On entering the room, the curious gaze of the ghoonghat–clad women gathered at the aanganwadi for the VHSNC meeting fell on us. With the room immersed in some amusing chatter and banter, Ms. Bhanu, the Lady Health Visitor (LHV) from the Nithawua Primary Health Center (PHC), introduced us to the community. We were greeted with smiles, nods, and namastes. The women repositioned themselves to make space for us to sit on the rug, neatly laid on the floor. After a brief disquietude due to our presence, Ms.Jayashree Panchal, the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) of the Aanganwadi, asked the LHV if she could begin the meeting in wagdi, a language in which she and the community members were comfortable with. As the LHV nodded assent, Ms. Jayashree Panchal set the tone by urging the participants to keep themselves hydrated and stay indoors, as Rajasthan was still reeling under a heatwave. Then, she advised the community to keep their surroundings clean and spoke about the upcoming monsoon season. She prompted the community members to voice their needs and issues, if any.

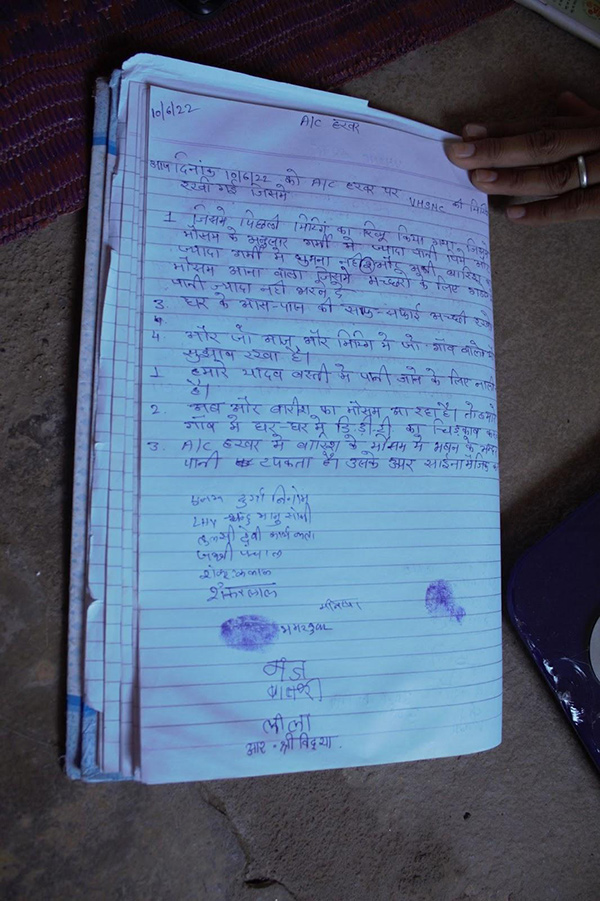

After some initial reluctance and silence, presumably due to our presence, the members began to warm up. With gentle nudging from Ms. Bhanu and Ms. Jayashree Panchal, we could hear faint voices and murmurs. One requested indoor residual spraying of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), another for waterproofing the Anganwadi roof with China mosaic before the onset of monsoon, while the others nodded in agreement. As the members voiced their issues, Ms. Durga Ninama, the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) of the Harvar health sub-center, took down the meeting minutes in a notebook.

While the meeting was in progress, what particularly caught our attention was the gender composition of the gathering. The gathering was predominantly female. Of the 13 community members gathered at the aanganwadi, 12 were women. Informed about the gender dynamics and power relationships of the region, we expected the sole male participant to initiate the discussion and lead the meeting. However, we were in for a pleasant surprise.

The NHRM guidelines call for 50% representation by women in each VHSNC [1]. Often, gender roles and norms make women more prone to diseases and risk of illnesses. Further, per the 2011 census, the female literacy rate is a dismal 43.60% against the male literacy rate of 72.68% in the Aspur block [3]. Consequently, more representation of women in such participatory health initiatives is a welcome change as it leads to women’s ownership of health and allied issues and encourages their participation in decision-making. However, would this gender inclusiveness, gender dynamics, and female participation in decision-making extend beyond VHSNCs?

Ms. Banu and Ms. Jayashree made efforts to engage each woman participant. Yet, only two or three women actively partook in the conversation while the rest timidly whispered among themselves. Ms. Bhanu then asked a middle-aged man sitting across from her if he had any concerns. He was the sole male participant in the gathering. As he spoke about the issue of water stagnation and mosquito infestation due to the lack of a sewer in the Yadav Basti, the discussion was sidetracked by the loud wail of an infant who had accompanied his mother to the meeting. The ladies blamed the searing heat and suggested the mother take him outside to get some fresh air. Although the anganwadi room was adequately ventilated, it did not have a fan. The discomfort caused due to the high outdoor temperature was apparent on the faces. A few ladies fanned themselves with the pallu of their sarees, and the kids who had accompanied their mothers and grandmothers to the meeting grew restless. The scene at the anganwadi of a mother breastfeeding her infant and a grandmother cajoling her crying grandson evidenced how taking time out to attend VHSNCs could sometimes be difficult for women due to their child-rearing duties, household chores, and gender roles. Whilst participatory approaches such as the VHSNCs enable women to assert themselves and exercise agency, attendance becomes arduous due to gendered mobility barriers and the burden of household responsibilities.

As the meeting resumed, Ms. Durga Ninama briefed the gathering about the interventions undertaken by the Harvar VHSNC. Activated in March 2021, the Harvar VHSNC started convening meetings only in Feb 2022, and this was their fourth meeting. However, the VHSNC had already made significant inroads within four months since the first meeting. The lack of a tarred road leading to the aanganwadi was one of the first issues voiced when the first meeting was convened. Ms. Durga Ninama informed the gathering that the Panchayat had passed a resolution for the construction of a road, and the groundwork of laying gravel was completed. Once again, the gathering’s attention deflected from Ms. Durga to two men entering the aanganwadi. It was the General Nursing and Midwifery (GNM) staff from the Nithuawa PHC and the Community Health Officer (CHO).

Ms. Durga continued with another success story of the Harvar VHSNC. The Panchayat recently built a boundary wall around a well next to the Harvar sub-center upon an appeal from the VHSNC. Thereafter, Ms. Jayashree took over from Ms. Durga to inform the gathering about another initiative currently supported by the VHSNC. Pointing to Ms. Manisha, a young mother with her infant, Ms. Jayashree remarked that she had not received cash assistance for the institutional delivery of her second child under the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and has approached the VHSNC. Ms. Jayashree added that the committee has submitted an arzi, and the mother would receive the cash soon.

When asked who writes the arzi, Ms. Jayashree and Ms. Durga looked at Ms.Bhanu and smiled sheepishly. Ms. Bhanu, as an LHV at the Nithauwa PHC, run by BHS in partnership with the Rajasthan Government, oversees the VHSNCs across the Aspur block. From time to time, she attends VHSNCs of different revenue villages that fall under the Aspur block. The reliance of the committee on an external facilitator like the LHV was evident from the interactions.

Later, Ms. Durga passed the notebook, in which she was taking the meeting minutes, around to take the signature or thumb impression of the participants, signaling the end of the meeting. After signing on the notebook, a pregnant woman and a lactating mother reported to Ms. Lakshmi Upadhyay, a poshan champion from the NGO IPE Global. The NHRM guidelines also suggest the inclusion of representatives from existing community-based organizations such as Self Help Groups (SHGs), NGOs, and Youth committees in the VHSNC for a holistic perspective [1]. Ms. Lakshmi measured the weight and height of the infant, his lactating mother, and the pregnant woman. She noted the measurements on an e-form and the Mamta card of the women, counseled them to eat green leafy vegetables, and showed an animated video in Hindi on the importance of eating and staying healthy during pregnancy and lactation.

Post-meeting, from our interaction with the ASHA of the center, we learned that the Harvar VHSNC consists of 15 members, seven males and eight females. Further, many VHSNC members did not turn up on that particular day as wheat was being distributed around the same time at the local public distribution shop. Ms. Panchal also mentioned that the composition of the meeting had predominantly been female in the last three sessions.

Although it is too early to appraise the performance and community participation of VHSNCs from the visit, our observations from the meeting have left us with many questions to ruminate about — What are the constraints faced by both men and women in attending VHSNC meetings? How does the gender role as caregivers for women and breadwinners for men affect their participation in VHSNCs? Does the participation involve the entire cross-section of the village community? Would the few women who voiced their concerns during the meeting still have been vocal had there been more male attendance? How does the presence of an external facilitator influence the dynamics of the meeting? In a place where the ghoonghat-culture is still prominent, do women face repercussions in their personal lives for voicing their opinions in the public sphere? We seemed to have more questions than answers at the end of the visit.

- An application

- Nutrition

- A mother and child care booklet designed for providing information to caregivers about care for pregnant, lactating women and 0-3 years of Children.

References

- Home :: National health mission. (n.d.). Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/vhsnc/Resources/Handbook_for_Members_of_VHSNC-English.pdf

- Basic Healthcare Services (BHS). (n.d.). Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://bhs.org.in/

- Home. (n.d.). Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://education.rajasthan.gov.in/content/raj/education/literacy-and-continuing-education/en/home.html